I read „unserveyed“ on the electronic chart and „Navigational Aids unreliable“. This is an exaggeration, because there are no navigational aids in the waters of the Bijagós – apart from the Geba River, where the cargo ships operate: no cardinal buoys, no danger signs, nothing.

With GPS and trust in God

A few fairway buoys, red and green, would be extremely helpful right now. I steer Blue Alligator, my Victoria 34, through a side arm away from the wide channels – through a belt of navigable water meandering between islands and sandbanks.

However, this belt is only visible on the display of my chart plotter: a strip of lighter blue that runs between the green of the shallows and the yellow-coloured areas that mark solid land. These shallows are invisible to the naked eye in the murky brown water, so I navigate by GPS and trust in God.

Leaving the anchorage at the Anchaca Lounge with the yacht Bluehemian.

Every now and then the bottom rises and the depth gauge reading drops below ten metres. I then steer slightly to the side and observe the readings. Is it falling or rising? I feel my way along like a blind man.

Dependent on the instruments

I realise how much I depend on the electronics on board. If they were to fail, I would be helpless. I do have a hand lead, an old-fashioned thing consisting of a piece of lead on a long line with markings. But how was I supposed to operate it and steer the boat at the same time? And anyway: I’ve never used it before and would have to practise first.

Following behind me is the Dutch yacht Bluehemian, which left the anchorage at the Anchaca Lodge on Rubane Island with me in the morning. The Dutch have sent me ahead, as a scout so to speak, because Blue Alligator has a draught of just under 1.50 metres compared to Bluehemian’s two metres.

The tidal current should actually be with us. But here in the narrow channels between the islands, islets and sandbanks, it doesn’t want to follow the rules. Sometimes it comes from the front, sometimes from the side, rarely from behind. And it is strong. Two knots are not uncommon in the Bijagós. It often reaches three knots at its peak.

Because we’re travelling in zigzags, we can’t always sail. The engine has to help us to make progress.

There are no up-to-date paper charts for the Bijagós. The electronic charts that I have downloaded to my plotter and iPad have to do the job. I use Navionics and follow the route that the programme has calculated in advance.

The route that Navionics calculated through the archipelago.

What seems a narrow fairway on the chart looks in reality like s wide stretch of water.

The map and GPS guided us safely to the first anchorage in complete darkness when we arrived on the Bijagós. But sandbanks wander and surprises are to be expected.

Sandbank ahead

I experienced one such surprise a few days earlier when I sailed into the relatively wide fairway from the island of Joâo Vieira in the south towards Ilheus dos Porcos. It was marvellous sailing and we approached our destination tack by tack. This time the tidal current also helped and Blue Alligator literally flew over the water.

I let the wind pilot steer and savoured the moment. I kept going down to check my position on the chart plotter and estimate when the next tack would be due. At one point, I must have forgotten the time. When I finally stuck my head through the hatch again and looked around, the water shot over a sandbank just a few hundred metres ahead. It hadn’t been marked on the map.

I tacked as fast as the sails would allow. If we had run aground, it could have cost me the rig. With fatal consequences.

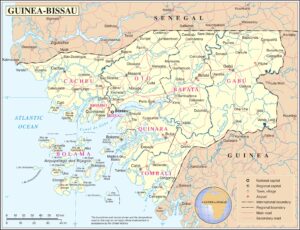

Map of Guinea-Bissau with the Bijagós archipelago. (source UN)

Major damage cannot be repaired on the Bijagós. Spare parts for the engine or rig are also hard to come by. Just getting hold of diesel is a matter of luck and effort. The people from the Anchaca Lodge on Rubane helped us, and we were glad they did.

They took us to Boubaque in one of their heavy wooden boats, which is powered by a powerful outboard motor. There we bought all the diesel that was in stock in a small, dark shop, just over 200 litres for three yachts.

Diesel comes in jerry cans of 25 liters in Boubaque.

The fuel was filled in 25-litre canisters, which did not inspire much confidence. Adelino Da Costa had warned me in advance. He had said that the quality of the diesel was dubious. He had therefore instructed the young salesman to give us a piece of foam to filter the fuel with. This presumably kept out the coarsest dirt particles. But we didn’t feel completely at ease when we filled our tanks.

We were able to order water in Bolama at Loja Verde, the only shop in town. It was also bottled in 25-litre canisters. The owner of the loja brought it down to the pier in his small van. From there we had to transport it to the yachts in our dinghies. The water was free. But we had to hire the canisters. The price rose continuously during our stay.

The loja verde – the green shop – in Bolama.

The helpful lodges

The water came from the village well directly in front of the shop and is pumped up with an old-fashioned swivel. After our cleaning in Bolama, we showered there like in a public bathing establishment. I used this water for cooking and washing the dishes. At best, I took the risk of brewing my coffee with it. It didn’t occur to me to drink it straight, although we were assured that it was drinkable.

Anchaca Lodge on Rubane.

At the Lodge Chez Claude in the national reserve of João Vieira and Poilão and the Anchaca Lodge, we were allowed to draw water directly from the taps. And we were also allowed to stand under the outdoor showers.

The two lodges welcomed us with open arms and a warm welcome. And they didn’t just help us to get diesel, water and supplies.

Grilled barracuda at Chez Claude on João Vieira.

Gaston, the taciturn accountant at the Anchaca Lodge, also organised the exit stamp for us. The day before our journey through the side canals, he had our passports taken to the airport, where they were stamped. We didn’t have to go to customs ourselves. And we weren’t asked to pay either.

Fear of people in uniform

Corruption may not be as pronounced on the Bijagós as in other African countries. But those who wear uniforms also like to take the opportunity to earn extra income, as a French sailor who was stranded in the Anchaca Lodge and now had the task of driving the staff there assured us.

The uncrowned king of the Bijagós, Adelino Da Costa, wants to take care of the problem. He promises to punish police officers who are at fault. The crews of yachts should feel safe. If anyone can curb corruption, it’s Da Costa. I was definitely glad to have saved his telephone number just in case. His voice alone works wonders.

The pictures from the receptions

But we had an ace up our sleeve: the pictures from the receptions in Bolama and Boubaque. When we arrived in the two towns, everyone who was somehow important came to shake our hands. When we reappeared off Boubaque after splitting the fleet into two groups of just four yachts, the police asked for written authorisation to sail the archipelago.

We did not have such a document, which of course costs something. We had never heard anything about it until then. But nobody could claim that we had sneaked in secretly, because we had the pictures from the receptions. We sent them to the police and they left us alone from then on.

Thanks to the official reception in Bolama and Boubaque the police left us in peace.

The police on the Bijagós don’t have any boats. That’s why we’re not afraid of unwelcome visitors on our last trip through the archipelago’s narrow channels. We reach the island of Caraxe in the north without incident in the early evening and decide to anchor there. We want to continue on our way shortly before midnight. As the evening progresses, the wind picks up and the anchorage becomes more uncomfortable by the minute. It is not difficult to leave.

Traffic and fishing nets

But now we are in the Geba River and the AIS, the Automatic Identification System, is constantly displaying warnings. I radio a few times to cargo ships that might cross my course. A voice with an Indian accent confirms that they want to avoid me. The officer with a more eastern european voice also wants to change the course of his giant ship so that the little sailor can continue on his way undisturbed.

It is more difficult with the fishing nets, which are stretched out in the still shallow water up to 30 nautical miles off the coast. They hang from buoys, jerry cans or plastic bottles. It is impossible to say where the „string of pearls“ begins or ends. It gets lost on both sides in the haze or between the low waves. I also don’t know how deep the net is that I’m heading for the following morning.

I decide to drive through it, switch off the engine and let Blue Alligator drift between two yellow canisters. I hold my breath, expecting to get stuck with the keel. But nothing happens.

Under storm jib to the Cape Verde Islands

There are still around 440 nautical miles to the Cape Verde Islands. I intend to head for the island of Sal in the north-east first and then continue to Mindelo. However, when I unfurl the headsail, I make an unpleasant discovery.

Blue Alligator has a so-called furling system. This means that the Genau, as the large headsail is called, is rolled up around a guide pole and can simply be unrolled from this when in use. The pole consists of several parts that are joined together. Two of these parts have come loose from each other.

I furl in the genoa a little and hope that it holds. Then I discover the real problem: the line used to hoist the genoa, the genoa halyard, had snapped at the top. I have no choice but to furl the sail completely – and I’m delighted that I manage to do this – and set the small storm jib.

Under storm jib back to the Cape Verde Islands.

The storm jib is no substitute for a genoa. It is a small triangular sail that, as the name suggests, is used in storms. Right now, however, the wind is rather light. There’s no storm in sight far and wide. But the small sail is better than nothing. Later, when the wind comes in from the side and even later from behind, the mainsail is sufficient. But we are travelling much slower than planned.

Heading for Sal has now become pointless. I wouldn’t find any repair facilities there. So straight to Mindelo on São Vicente. After five days, I approach the island from the north-east. The city lies to the west, nestled in a deep bay and protected by the large neighbouring island of Santo Antao.

I approach with dramatic slowness. It is not until midnight that I reach the northern entrance to the channel between the two islands. And there the wind picks up considerably.

It is the typical acceleration zone between two land masses that also makes life difficult for sailors in Cape Verde. Especially when they are travelling in pitch darkness and only have one light for orientation, the beacon on the Ilheu dos Pássaros directly in front of the entrance to the bay.

Distances are difficult to judge at night and the passage between Ilheu dos Pássaros and Ponta João Ribeiro, which marks the outer end of the bay, seems to have shrunk since the last time I was here. As I lower the sails and therefore put the boat into the wind, I’m afraid of running aground at any moment. Of course, the mainsail won’t just fall. I have to rush back and forth between the mast and the cockpit several times to retrieve the sail. I look anxiously over my shoulder and see the shore approaching. Finally, I can cast off and steer back into the bay.

I motor to the anchorage. It has filled up since our last visit at the beginning of November. The sailors who want to cross the Atlantic have arrived. I have to look for a suitable spot and do several rounds. It’s now after two o’clock and tiredness is making itself felt.

That’s probably why I don’t see the hull of the wreck, which lies shiny black like a whale’s back in the middle of the anchorage, until the last moment. I steer hard to port and we just manage to pass it. I finally drop the anchor behind the wreck.

I’m back in Cape Verde. The Bijagós adventure lies behind me. It’s the 5th of December 2023.

Pingback: Durch schmales Fahrwasser - Meergeschichten

What a wonderful blog to read, so you can now enjoy the special period in Bijagos again

Thank you Renita!