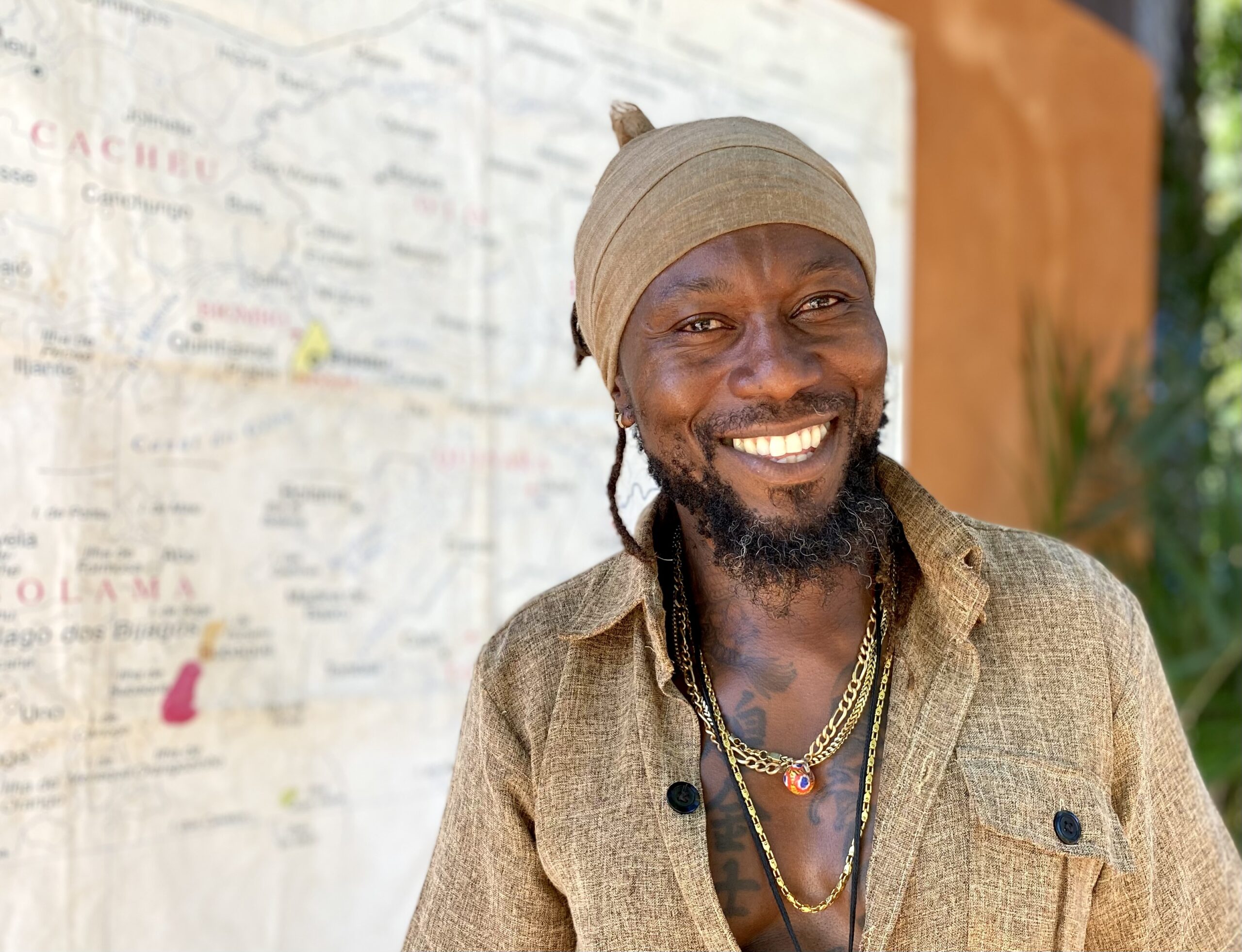

At the beak-shaped bow of the narrow, long boat stands a man with a fiery red headscarf, upright, looking forward like a king or commander heading for a shore he intends to take possession of. He is also wearing an elegant black shirt, which sets him apart from his companions in their washed-out T-shirts. The man’s name is Adelino Da Costa and he is indeed a kind of king, the uncrowned king of the Bijagós.

Palm wine instead of beer

When Da Costa’s boat sailed past the anchored fleet of our yachts across the brownish water that day in November 2023, I already knew him. I had met him in Bolama after we had been welcomed there by the honourables and completed our formalities. On the second evening in the former colonial town, Da Costa had organised a dinner for the crews. We sat under the shady trees at the harbour at an improvised table and he had rice and a stew with chicken and antelope meat served. Da Costa himself was not above filling the plates. We helped with the serving.

Instead of beer or coke, the host distributed lemonade and palm wine on the tables, just like the simple people in the villages drink on the Bijagós. Why bring drinks or supplies when the local food tastes just as good, said Da Costa. I know palm wine from my trips to India and am not very fond of it. But the lemonade was excellent. And as the drinks were poured from old plastic bottles, we didn’t leave any extra rubbish behind.

The rubbish collectors from Boubaque

I wasn’t to have the opportunity to speak to Da Costa in detail at that time. And before I could do so, two days later he took us through the second village on the Bijagós, Boubaque on the island of the same name. The settlement is little more than a collection of single-storey buildings on streets littered with holes and rubbish. But there is a hospital in Boubaque, where we dropped off the first of our bags of clothes and medical supplies that we had shipped across the sea. And in Boubaque, an organisation is trying to get to grips with the rubbish that plagues the archipelago in an endless stream.

This organisation exists mainly because it is supported by Da Costa. He introduced us to the people in charge and had them explain what they do with the rubbish. What is recyclable is recycled, said one employee, for example lamps or containers are made from it, which they try to sell. But plastic cannot be recycled and the young woman shrugged her shoulders somewhat resignedly. It is collected in the forests and burnt. Later, we drove past the charred remains.

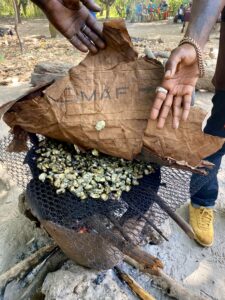

To keep the oysters they are smoked in the villages.

Mussel shells pave the paths

From Boubaque, Da Costa took us to a village deep in the island’s forests. The further we travelled from the town, the less plastic waste there was. Instead, shells piled up around the village to form veritable mounds. The paths were also plastered with them. And between the simple huts made from clay and straw, women smoked oysters over small fires to preserve them.

Da Costa shows the rice granaries in the village.

Da Costa also showed us the rice fields surrounding the village and the granaries where the harvest is stored. „They have everything they need to live here“, he said. And to prove that the food is not only sufficient, but also tasty, he had another dish served: grilled fish, served with rice fried in palm oil and oysters. The dish would easily earn a place on the menu in a Michelin-starred restaurant.

Grilled fish and rice with smoked oysters. A wonderful dish.

But why did Da Costa do all this for us? And above all, who is this dazzling figure in his eye-catching costume, with the piled-up Rasta hairstyle and a permanent smile on his face?

The boxing champion

Adelino Da Costa is 47 years old this year. He comes from an island at the mouth of the Geba River. This marks the northern border of the Bijagós archipelago and leads to the capital of modern Guinea-Bissau, Bissau. The Manjaca people live on Jeta. When he was ten years old, his mother brought Da Costa first to the capital town Bissau and later to Lisbon so that he could go to school there. In Lisbon, however, the family lived in a favela, as we know it from Brazil, a slum. Violence was commonplace.

The Manjacas are fighters. Children, young men and even women wrestle with each other in rituals. It’s part of growing up. And so it was obvious for the young Da Costa to fight in order not to get lost in the everyday life of the slum. However, he didn’t do it like a street urchin, but with discipline and a system. He began to train. „In our culture, fighting is a question of inner attitude“, he says, and fighting may indeed be at the core of his nature, even if there is nothing violent or brutal about him. On the contrary: you can sense a warmth that has nothing artificial about it. He makes it easy to feel comfortable and relaxed in his presence. But there is always this attitude: slightly crouched, lurking, as if he is ready to attack at any time – or to defend himself.

Success in New York

And Da Costa was a very effective fighter. He rose to become the Portuguese champion in thai and kick boxing. He later began training teenagers. But he wanted to get to the top, therefore he moved to New York, because anyone who wins there is one of the best. And Da Costa won and became champion in the USA too. This brought him money, which he used to open his first fitness centre. More followed, closer and closer to the centres of power and wealth. Having arrived in the heart of Manhattan, Da Costa had reached the pinnacle of an extraordinary career. He could have left it at that. But he had other plans.

„I wanted to give something back“, he says in the interview. That’s why he returned home to Guinea-Bissau in 2008. That sounds a bit cheesy. But it shouldn’t be an outright lie, not one of those hackneyed phrases that investors use to disguise their greed for profit. At the same time, I am convinced that not everything the champion does is purely altruistic. But that doesn’t make him a bad person. Just a contradictory one.

Adelino Da Costa has entered the tourism business on the Bijagós. He owns two lodges on the island of Boubaque, is planning a hotel on a leased island – in exchange for a motorbike, zinc sheets for roofs and a well with an electric pump – as well as another lodge near Bissau. Two fitness centres in the capital are also part of the empire. My fellow sailor, the anthropologist Paulo, reports that the walls there are adorned with reports from newspapers and magazines, all of which tell of Da Costa’s life. A less self-absorbed person might have done without them.

We are not invited to visit the Dakosta-Eco-Retrait on the island of Boubaque. During the rainy season, storms had caused major damage, which is now being repaired for the season, the explanation goes. The pictures and videos I see of the lodge show lots of young, good-looking people who naturally all make a happy impression.

Millionaires for a good cause

Some of these people are famous, Da Costa tells me. He wants to get celebrities in front of the camera because they attract other celebrities, says the champion candidly. „I want to attract millionaires“, he says, because they would invest in projects that save the Bijagós, projects such as waste disposal.

The chances of him persuading the rich and famous to visit the Bijagós are not bad. After all, Da Costa is rich himself and also an attractive man. He also has excellent contacts among the country’s elite and in Portugal. I have not the slightest doubt that he will achieve his goal of presenting the Bijagós as a fragile paradise at international tourism congresses.

When I ask him if he also has a dark side, he thinks for a moment and then replies: „I always give too much.“ I try again, alluding to his extravagant clothing. This is also a sign of respect, Da Costa replies. But, he admits, he simply feels comfortable when he is well dressed. He then adds another sentence: „How can you make others feel good if you don’t feel good yourself?“

Will the Bijagós become a Disneyland?

Sustainable tourism, local food for millionaires from Europe, the USA or wherever, investment in waste disposal and jobs for the locals. This is roughly the mix with which Da Costa wants to do something good for the Bijagós and at the same time preserve their traditions and ancestral ways of life. I am sceptical. Won’t that turn the islands into a Disneyland, I interject.

Da Costa shakes his head. That depends on the attitude of the visitors. If they treated the locals with genuine interest and respect, the Bijagós would certainly not become a Disneyland. Instead, it could help people of the islands to appreciate the value of what they have and how they live. „Our opportunity is that we are lagging behind here“, says Da Costa. In other words, it is easier to preserve something than to rebuild it.

If you go into the villages, you often meet people who look at the white visitors with sceptical eyes. And some would even disappear into the forests during the tourist season to avoid contact, it is said. Perhaps this is a chance for Da Costa’s vision of two worlds that can exist side by side to become a reality – in the will of the people to remain true to themselves.

A young man on the island of Robane. With the stick and the sling he climes palm trees to collect the fruits for oil.

„I am still doing too little“

Who knows. But I suspect that every tourist who turns up in a village with a smartphone and wearing functional clothing also arouses desire. And Da Costa is by no means the only tourism entrepreneur on the Bijagós. There are various lodges on the islands where people drink beer and wine. The waste they produce is incinerated out of sight of visitors. I meet Da Costa in one of these lodges and ask him how he feels about the lavish luxury in the midst of the island’s splendour. „I feel that I’m still doing too little“, he replies spontaneously.

The uncrowned king Adelino Da Costa also has two princes, aged 12 and 15. They live in the USA and are reluctant to come to the islands. But they will one day inherit the legacy that Da Costa will leave behind. „When you are the son of a king, you know that you will become king yourself“, he says. He does not want to allow an alternative. I dare to counter with the question of free will. „You can see where free will has taken our world“, he replies, smiling his winning Da Costa smile.

The princes will have to wait a little longer before they can follow in their father’s footsteps. „I want to live to be 160“, says Da Costa and he seems to mean it. The healthy food and life on the Bijagós should help him achieve this.

We sailors were also given a role in the plans to develop the Bijagós that we initially had no idea about. In the course of our „mission“, however, it became apparent. More about this in the next blog.

Pingback: Der König der Bijagós – Meergeschichten

Pingback: Tourism instead of plastic - Meergeschichten

Pingback: Sailing through narrow waters in the Bijagós - Meergeschichten